|

|

|

|

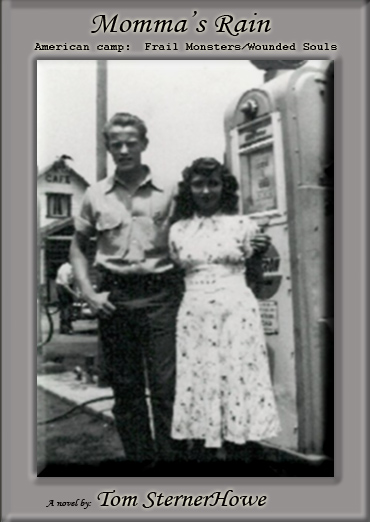

American Camp:Frail Monsters/Wounded Souls: Momma's Rain |  |

|

Chapter One: Children In Passing

For life is a fiction birth a sad truth death a just rewardstill Children smile Chapter One: Children in PassingI don’t like Country Western music Billings Montana Winter, 1957 It was a cold little house, full of shadow and dark windows. There, Daddy was drunk and Momma was crying. I always loved him and hated him for making her life miserable. I bit my lip and held my breath, then went where I was forbidden to go. The door, usually stuck tight, opened easily. I took this as a good sign, an acceptance of darkness. I slipped inside and eased the door closed, knowing my eyes would never adjust to the total pitch black but waiting anyway -- standing on that top rickety step as soft things with sharp teeth scurried below. Some thing with many feathery legs lit on my forearm, skittered across the fine blonde hairs on the face of my skin, its movement lighter than breath. My voice screamed inside but no sound issued forth. I rubbed my arm in that spot, felt the tiny arc of weight the traveler of darkness made as it swung from the pendulum web it had launched on my skin.

The odor in that place was darker than ink. I breathed in deep and took the first step down. What damp embrace the womb of that room offered. It was warm in its Earthen reek of soil, timeless and rotted root, kind to those who crawled and climbed, huddled in its midst. My small hands grasped the wobbling plank at the side of the staircase, and its nails creaked as I leaned in with my full weight. Feet hanging, I searched with a naked toe through the broken top of my shoe for the first of the climbing holes we’d made, my brothers and I. There... and there... I let loose the plank and dropped to the Earthen embrace of the floor. Back to the wall, I finally let the tears come, hot and salty, forging watery paths on the planes of my cheeks. This wasn’t my first experience with shame, I know, but it was much like times before and since forever. Seven years old, with two younger brothers and a baby sister of two, I knew I had to be brave. Crying would only make things worse; there was never a reward for tears. I hugged my legs to my chest, then sobbed and sucked it in, a choking sound. I held my breath as my ears picked up some sound outside of self. Squeak ... squeak, squeak. I exhaled an audible sigh. I could hear Jerry, my best brother and only friend, a year younger than myself. I was older but he knew things, things I would like to argue away, but couldn’t… I felt a smile tug at my lips as his voice spoke in my head. “They’re doin’ it, Timmy. Long as they’re doin’ it, they won’t be botherin’ us.” I covered my ears with my hands as the cadence of the squeaking increased. Dust drifted down from the floorboards above, a blessing of sorts from mother to son. I stood and brushed myself off, knowing she would seek me out after the squeaking. The climb holes were easy enough to find, and I hoisted myself up until I could grab hold of the old plank. A sliver went in under the nail of my right index finger. I gasped and swung my foot up to the step. A thin shaft of light made its way from the kitchen through the top edge of the door. I found the knob with my throbbing hand, twisted and gave a slight nudge with my shoulder. Now it was stuck. I gritted my teeth and fought back the urge to cry out. Just as I was ready to try again, the door opened slowly. My mother took a step back, hands on her hips. “Timmy, you come out of there. How many times have I told you...” She paused, then lifted her thin arms. “You’ve been crying.”

Relief flooded over me as I fell into her embrace. The top of my head reached her chin and I nestled in, wishing for time to stop, no words. Just hold me on the mercy of your sweet breast. She pushed me gently away. “What were you doing down there? If your dad ever catches you...” I held up my finger. “It hurts.” She took it between her hands and raised it toward her face. I giggled as her eyes crossed. “What?” she demanded with mock sternness. “Your eyes,” I replied. “They got all crossed up.” She held my finger tightly with one hand, and plucked deftly at the splinter with the other. Before I knew it, she’d kissed my injured fingertip and was pumping water, washing it off in the kitchen basin. “Now, what were those tears about?” I held up the wound. “It hurt real bad,” I explained. “Don’t lie to me, Timmy,” she scolded. “You know you’re no good at it.” I looked down at my toes, wiggling through the top of my shoe. “Why’d he have to whip Jerry so hard?” Momma stood up straight, arms akimbo. “Your brother got just what he deserved. He was caught sneaking into the bread and ate the last two slices. What am I to put in Daddy’s lunch tomorrow? It’s cold on the roof and he needs food to keep himself going. He doesn’t get paid until the roof’s finished.” “That’s why I was crying,” I said stubbornly, remembering the crack of the belt on Jerry’s bare skin while he bent over and held his ankles, trying not to fall over or cry. Momma shook her head, frustrated. “I’m going to lay down and have a nap. I have to go to work in a couple of hours. You keep an eye on your brothers and little Lisa. Wake me up at six.” She went back into the bedroom with Daddy. I left the tiny kitchen and went to the cramped living room, which served as day room and bedroom for Jerry, Peter, Lisa, and me. Us three boys slept on a convertible couch. Lisa had a makeshift bed in an old dresser drawer. Lisa was asleep and Peter was sprawled on the sofa. Jerry stood slumped in the corner where he’d been placed for further punishment. I lay on the floor so as not to disturb Peter. I bit down on my finger to alleviate the throbbing, then put my arm under my head and hummed myself to sleep. At five thirty I awoke and put a fire on low under the old coffee pot. I went back and sat on the end of the sofa, put my hand on top of Jerry’s head. His carrot-red hair stuck out between my splayed fingers. “Sorry he spanked you,” I whispered. Jerry groaned and pressed his small thin face into the hard scratchy corner of the wall. His hands bunched up against the wall, causing his shoulder blades to stick out. He looked like a broken bird, a plucked chicken, too skinny for anyone to eat. I went to my parents’ bedroom and entered quietly. I would watch them sometimes, faces moving, eyes twitching. Asleep, they were faces I didn’t know. I think maybe I liked them better that way. I reached and touched my mother’s shoulder. “No,” she mumbled, “no.” My dad’s eyes popped open. “Timmy, what are you doing?” The radio was playing Country Western. We had two radios, one on the kitchen table and one next to my parents’ bed. Oh yeah, and one in Dad’s old truck. The radios in the house were on twenty-four hours a day, always tuned to a Country Western station. The one in the truck was only on when the truck was running ... I think. They were on whether my parents were home or not. Kids don’t touch radios. “Wakin’ Momma,” I replied. “It’s just about six.” He rubbed a strong weather-beaten hand across his bleary eyes. “Shit! You go on, Timmy. I’ll get ‘er up.” I left the room, and he began to shake her arm. I have always gotten on fairly well with my mother but waking her or simply being around her when she wakes up are experiences I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy. She is not nice then, and needs to be left alone. One hour up, maybe more, then she becomes her almost agreeable self. So, I left them to it and went to play with my little sister who had just turned two. She was a cutie, the first girl after three boys. My dad called her Punkin. I tickled her and she giggled until I felt Jerry glaring at me. He treated me bad whenever he got punished, like it was somehow my fault or like he was receiving whippings on my behalf. I don’t know. He took the bread; I didn’t. All he could do was look at me mean and stare at me accusingly since I was bigger and a lot stronger than he was. Mom says when I was a year and a half old, (I’m fourteen months older than him), I would sneak in, take the top off his bottle, and guzzle down his milk. Catching me copping his food explained part of the problem with his thinness but she resented him anyway. No matter what she did, he was unhappy and undernourished. I heard the volume on the radio go up and the familiar clink of glass as my mother filled their coffee cups. Smoke drifted through the wide arch between the living room and kitchen as our parents lit their Pall Malls. Dad came into the room and plinked Jerry in the head with his finger. “Get your ass standing up straight. You don’t need to slouch around all day like a ninny.” I felt bad for Jerry as he cringed and shook with fear. “Turn around and come here,” Daddy ordered. Peter was still sleeping, one leg hanging off the couch. As Jerry rounded the corner, his eyes riveted fearfully on Daddy’s hands, he bumped into Peter’s leg. Peter moaned, rolled over, fell off the couch, and began to cry. Daddy beckoned to Jerry with his finger. “Come here, asshole. Maybe I’ll knock you to the floor; we’ll see how you like it.” Jerry stood by the side of the sofa trembling. “No Daddy, please no.” I saw a dark stain running down the front of his trousers and hoped our father didn’t notice. Sometimes when Jerry was in trouble he would mess himself which would only exacerbate his circumstances. Other times, when he wasn’t in trouble, he would mess himself which would start trouble anew. “Tim,” Momma called from the kitchen, “Come on now. I’ll be late for work.” Daddy pointed his finger at me. “You put that little asshole in the corner and don’t let him out until I come home, understand?” I nodded my head. “Yes, Daddy.” The door slammed and I heard the sound of Daddy’s old truck pulling from the curb. Jerry turned and looked at me. “Let me out of the corner.” I felt tears coming to me eyes, bit down on my finger to stop them. “I can’t, Jerry. He’ll find out, then we’ll all be in trouble.” “How’s he gonna find out?” Jerry challenged. “Who’s gonna tell?” Peter sat on the edge of the couch. “I will,” he said, a cruel grin on his little-boy face. “I’ll tell ‘cause you took the bread an’ got me in trouble. It’s all your fault.” Jerry took a step from the corner, threatened Peter with a raised fist. “I’ll pound you, you little brat! You ate half!” I ran between them and shoved Jerry back into the corner. I gave his head a good bump against the wall for good measure. “Stay there! Don’t be picking on smaller kids!” “Yeah!” Peter agreed smugly. “You’re a stealer, Jerry. You’re bad!” Lisa began to wail, evidently upset by all the commotion. I picked her up and she stuffed a thumb in her mouth. She snuggled against my chest and closed her eyes, sucking contentedly. Daddy didn’t come home after taking Momma to work. We were hungry, and there was nothing in the house to eat. I pumped some water and we sipped at it but water is a poor substitute for food. Lisa and Peter cried and Jerry moaned and groaned, then finally slid down the wall and rested in a bony pile. I roamed around the confines of the shack, despairing for a crumb but, as on many a previous night, there were none. I heard a rattling at the door and peeked out. It was Momma come home from work. As I unlocked and opened the door, a car pulled away. It was soon lost in its’ own steamy exhaust in the freezing winter night. “Where’s Daddy?” Momma asked upon entering the house. “He never came back,” I replied, “I been worried.” She kissed me on the forehead and handed me a heavy paper bag. “Never mind,” she said, “Thank God for the Big Boy.” Big Boy was the restaurant where Momma worked as a waitress. She wasn’t allowed to take food home but she would bus the tables she waited on and dump the leftovers from the plates in a bag she kept hidden in the kitchen. On nights when Alvin, the cook, brought her home she could sneak the bag out past the owner. The next trick was getting it past Daddy; he didn’t approve of his family eating garbage. Momma touched my face with her cold hands and kissed me again. She glanced at the clock radio wailing Country Western. “Twelve thirty,” she murmured, “He’s probably at the bar. That gives us ‘til two to eat. You start sorting and fixing. I’ll get the kids.” I set the bag on the table and opened it. Though it was full of rotting salad, coffee grounds, and cigarette butts, all I could smell was food and best of all... meat! I grabbed a piece of chicken fried steak and wolfed it down, coffee grounds, cigarette ashes and all. I’ve never tasted better food. Momma came back into the kitchen and smiled at me while I wiped my face on my shirt- sleeve. “I decided to let them sleep while we get everything ready,” she whispered. “Tonight we’ll have a feast. I see you found the steak.”

We scraped cigarette ashes, egg yolk, coffee grounds, and soggy napkin off the meat, and began to warm it in a pan on the old stove. We even managed to salvage some mashed potatoes and corn on the cob from the bottom of the bag. The cigarette butts went in Momma's apron pocket to be worked on later. We didn’t have to wake my brothers and sisters. Peter and Lisa came stumbling into the kitchen, their noses following the aroma of food cooking in the kitchen even before their eyes were ready to open. Momma smiled. “Go get Jerry.” He was standing up straight and stiff, nose stuffed into the corner. He flinched as I touched his arm. “Come on,” I whispered, “Momma brought some really good stuff.” He turned his head, eyes big and round. His mouth made one word. “Daddy?”

I tugged at his shirt-sleeve. “Come on, Daddy’s not home yet. You better hurry up!”

“Wait!” he pleaded. “Is she... Is she in a good mood?” “The best,” I replied, “Now come on.” Jerry shielded his eyes from the light as we entered the kitchen. We ate and ate, then sat around burping and smiling like contented chipmunks. Suddenly Momma held her nose. “Jerry!” she accused, “You have peed and messed yourself!” “It’s when he was scared, Momma,” I interjected. “Before you and Daddy left.” Jerry’s eyes were wide, like an animal caught in the headlight beams of a car. “Get out of my sight!” Momma ordered. “You’re disgusting. Scared is no excuse; we all get scared but don’t go around shitting ourselves.” She turned to me. “You’d better stop trying to stick up for him. You’re not really helping and you only run the risk of getting yourself in trouble.”

As Jerry was leaving the room, there was a loud bang on the door. “Oh my God!” Momma exclaimed, “he’s home. Timmy, get the bag; shove everything in it. I’ll try to keep him busy. You just...” Glass shattered and the door caved in. “Daddy!” Lisa called excitedly. He staggered into the room, squinting his eyes against the light. “C’mere Punkin.” Lisa ran forward and hopped into his arms. “Wassa matter?” He held Momma with an evil grin. “What I bring home ain’ good ‘nough? Your boyfrien’ Arnie been fuckin’ you in the garbage, then you bring it home to feed my kids, huh? Here, Timmy. Hol’ this baby girl for me.” I took Lisa and he backhanded my mother to the floor. It’s not the first time I hated my father. I was seven and a half years old; I believe it was the first time I realized I would probably have to kill him someday. And I would love him when I did it. Stay down, I thought as she knelt where she had fallen. If you get up... She got to her feet and he slapped her down again.I carried Peter and Lisa from the room, around the corner from our bleeding mother. “So!” My father trailed after us. “Where’s that little shit?” He went to the corner and plinked Jerry in the head with his finger. “Leas’ this l’il bastard stayed where I tol’ ‘im for once.” Jerry was trembling awfully; I could hear his teeth rattling. “Tim,” Momma laid a hand on Daddy’s shoulder. “Come to bed now, Honey. Come on... please.” Her tongue flicked at the blood flowing from the corner of her mouth. My mother was beautiful and wore her fear well. Daddy plinked Jerry again. “Don’ relax, you l’il bastard; we gon’ pick this up tomorrow.” He followed Momma through the kitchen and into the bedroom. The door slammed, followed by several slaps, screams, and thudding sounds. I rocked my little sister in her dresser drawer while the bed-springs began to squeak. Jerry was right; now we were safe. He turned and stared at me from the dark hollow holes of his eyes. Peter and Lisa were sound asleep. Jerry’s eyes bored into me. I was sad and ashamed, and had no idea why. “Where are your brothers?” I looked up into Daddy’s face. Momma was standing behind him, one eye black and closed. Her lips were swollen, cracked, and dripping blood. I sputtered and looked around the room in confusion. Ten minutes later I was across the street in the park with Momma. The lilac tunnels of summer were closed, their bare branches locked, intertwined and reaching, hands empty. The sky was slate gray, a vast condemning face looking down, seeing through the futility of our search. I shivered and felt my eyes tear up as I realized they must be out here somewhere. I closed my eyes and opened them quickly because Jerry’s eyes were in there. They had told me last night they would be leaving; it was my fault my brothers were gone. Momma and I followed two small sets of footprints in the fresh snow. They led us into the park, down to the round empty swimming pool. I had a pocketful of cigarette butts. Gathering them from gutters and walks since we began the search was natural for me, an old habit from my first memories. We would take the butts home where I would help Momma empty and grind them together; then she would roll them into smoking sticks for herself and Daddy. Momma was crying, and the wind had begun to blow. Tears were frozen on her battered face. We went home and found Daddy sitting in the dark little kitchen next to the old stove. Lisa was sitting in his lap. He had a cold beer in one hand, a Pall Mall in the other. “It’s only been a couple of hours since we got up,” he stated flatly, “If we don’t hear something, say by noon, we’ll call the police.”

“But they may have been gone half the night,” Momma protested.

“Don’t think so,” Daddy replied, then to me, “When did you go to sleep, Timmy?” “After you,” I replied, “I was rocking Lisa, then went to sleep. Jerry was in the corner and Peter was laying on the sofa.” Momma paced back and forth a bit, then, “I’m going to the corner store. Maybe they’ve been there. Can I have a dime for the phone?” Daddy set his beer down. “I’m not made of money, woman.”

“I... I gave you my tips last night,” she stammered. “There were dimes and nickels.”

Daddy set Lisa on the floor where she began to roll empty beer cans around. “Choo choo... choo choo. Lisa make train. Choo choo.” Daddy leaned back in his chair, reached deep in his pocket. I was afraid of the look on his face. He threw a handful of change in Momma's general direction. “I make more money by accident than you do on purpose, you stupid bitch. Take your nickels and go call the cops. That’s all you want to do anyway.” I scrambled to help her pick up the change. We hurried out the door and down to the corner phone booth. Momma began to cry and held me close as she spoke to the police dispatcher. When we got home, Daddy said the wind had blown the clouds away and made it warmer. He was going to pick up his helper, a man he called DeeDot, and try to finish the roof he’d been working on. He left, and I kept an eye on Lisa while Momma straightened the house. Two policemen came and asked Momma a gazillion questions. To my surprise, they took me out to the police cruiser and said, “Do your Momma and Daddy ever hit you and/or your brothers and sisters?” To which I lied, “No Sir.” “What happened to your Momma's face?” To which I lied, “I don’t know.” “Are you afraid of us?” To which I answered truthfully, and with relief, “Yes, awfully.” “Are you afraid of your parents?” To which I lied, “No Sir!” And so on; I was seven years old and knew better than to cooperate with the police. They seemed to stay for an awfully long time and, before they left, they promised Momma they would broadcast a story about the two missing boys on the television news. The only picture she had to give them was of Peter after he drowned in the irrigation ditch the year before. He looked cute sitting in the hospital crib. They sent a lady out later who drew a pretty good picture of Jerry from Momma's description. We didn’t have a TV, so we didn’t see Jerry and Peter on the Billings News. Daddy saw it though, on a television at the bar. He was upset over the broadcast, since the newsman said police had yet to interview the father; a statement which, to him, implied suspicion. If Peter wasn’t missing, I would have been suspicious myself. Daddy seemed to favor his youngest son as much as he despised Jerry. To say I feared for Jerry is somehow making light of that emotion, the frail breath of our lives in general. Fear was a tangible aspect of our day-to-day existence: fear they’d throw Daddy in jail when he was drunk, fear they’d let him out when they did, fear he’d hurt Momma. Most times fear would even dispel the rampant rumble of our ever-present hunger, fear that Daddy had killed Jerry. The next day Daddy had to go the police station for an interview. A nice lady came by and gave us commodities; we had Cream of Wheat for breakfast and Spam for lunch. Momma stayed home from work, and I didn’t go to school. She was so fidgety and nervous; she kept crunching up the cigarette butts. Her hands shaking so bad; she wrecked them in the roller. She’d come and hug me, again and again. “You’re my big strong boy, Timmy, my big strong boy. You’ll never run away from your Momma.” Daddy came home in a terrible mood. It was fairly warm, so he sent me outside to play with Lisa. Our house sat on the edge of a tiny courtyard along with a half dozen other one bedroom rentals. There were lots of toddlers and Lisa, being an agreeable and sweet child, joined right in and began to play with them. I sat and watched her, thinking about a girl in school I liked. She wore glasses and was real smart. I couldn’t see the blackboard, and she would whisper assignments to me. Sometimes after school we’d meet on the corner. She’d take off her gold necklace and we would swing it round and round between us while we talked. She was my very first crush, and her name was Jackie.

That night, the second night my brothers were gone, Lisa and I were sent to bed at eight o’ clock. Momma hung a blanket across the archway between the rooms. I snuggled up with Lisa on the couch and listened to the hushed tones of my parents talking. I couldn’t distinguish the words over the music from the Country Western clock radio. I sensed an urgency in the gist of the conversation and, worst of all for a child, parents afraid of circumstances set in motion over which they had no control. The next morning we were awakened by police at the door. They showed Daddy a paper and asked him to turn the radio off so they could talk to him. He did as they asked but Country Western music could be faintly heard from my parents’ bedroom. I could tell Daddy was mad, but he didn’t say anything mean to the policemen. There were six of them this time. They looked big and threatening in our tiny house. One of them even had to bend over to keep from bumping his head when he passed through the arch into our sleeping space. Lisa and I sat in the corner while two policemen lifted the couch and shined their lights underneath it. The big one shook his head. “Cockroaches.” His partner lifted mine and Lisa’s cover from the couch, then dropped it disdainfully. “Infested with bedbugs,” he said as he cast us a sympathetic glance. His sympathy was lost on me; I was embarrassed and afraid. “Hey, Sarge.” a voice from the kitchen, “come check this out.” To my surprise, the smaller policeman answered the call. I thought the big one would be the boss. Lisa wiggled in my lap and tried to follow them, but I held her tight and tickled her to create a game and keep her busy. “Timmy, come here,” Momma called out. I stood and hoisted Lisa up onto my hip. She was a chunky girl. It took a lot of courage to lift the edge of the blanket and pass from the security of the living room into the tiny kitchen packed with grownups, but I managed the task. The policemen had opened the door to the dirt room, and were huddled around the opening. They were pointing their long powerful flashlights down into the gloomy space. “So you say you’ve never been down there,” Sarge said to Daddy. Daddy sat at the kitchen table, one leg crossed over the other, drinking coffee and chain smoking Pall Malls. “Nothing down there but dirt,” he replied, “I was gonna store shingles and tools down there, but the steps are broken; it’s not worth the trouble to fix them.”

“How ‘bout the kids?” the policeman pressed, “Do they go down there to play?” “No way!” Daddy said indignantly, “There’s bugs and stuff down there. I wouldn’t let my kids go where I wouldn’t go myself.” “Someone’s been down there, Sarge,” one of the policemen interrupted. “Timmy,” Momma said, with a flat edge to her voice. “It was me,” I croaked, “I climbed down there yesterday.” “Damn it, Timmy!” Daddy scolded, “I told you...” “That’s enough!” Sarge leveled a warning glare toward Daddy, then turned to the other policemen. “Bentley, get those shovels out of the car.” His gaze returned to Daddy. “You’re a roofer?” “I’m a roofer,” Daddy replied defeatedly. “You wouldn’t happen to have a ladder that would fit through this door, would you?” Sarge asked. “Timmy,” Daddy said, by way of reply, “Go get the chicken ladder off my truck.” A chicken ladder is a handmade wooden ladder that roofers use to climb up the face of steep roofs from a plank scaffold. I left the room with relief, elated to have something to do. The cold Montana air felt great in my lungs as I squinted my eyes to shield them from the sun. There were police cars blocking the courtyard, and the neighborhood men were huddled off to one side smoking cigarettes and staring at our house. I felt uncomfortable under their gaze, and ignored them as best I could while I twisted the shingle wrapper wires holding the chicken ladder and slid it off the wooden rack of Daddy’s truck. “I got it, kid.” I jumped and banged my head on the truck rack at the unexpected sound of a voice. The big cop grinned and patted me on the head. “Sorry kid, thought you knew I was behind you.” He picked up the heavy two by four ladder like it was light as a toothpick and carried it into the house. He poked the ladder through the doorway, down and into the dirt. Someone had rigged a hundred watt trouble-light to better see, and spiders skittered across the broken shelves of the old root cellar.

“Got anything to say before we go down there?” Sarge asked Daddy.

Daddy stood up and put on his hat. “Yeah, I got a roof to put on.”

“Sit down!” Sarge growled. “You’re not going anywhere until I say so.” Daddy sat down but kept his hat on. Two policemen set their heavy belts with gun, night stick, and flashlight in the corner by the stove. They set their hats on top of the pile, threw shovels into the hole, and followed them down. They worked in twos, digging sideways and down, until late afternoon. The kitchen floor was crusted with dirt and mud, the air close with the heat and palpable tension of too many bodies in too small a space. Sarge ordered the men from the hole and sat down wearily across the table from Daddy. “Where are they?” he whispered in exasperation. Before that day, I had never seen Daddy cry. He took a handkerchief from the back pocket of his trousers, and blew his nose loudly. He looked imploringly at the policeman. “God as my witness, sometimes I’m not much of a husband or father but, I would never hurt my children. Please go and find my little boys.” Sarge stood up. “Oh, we’ll find them; you can bank on that. Let’s just hope we find them in one piece.” Momma was scooping up dirt with a piece of cardboard and dumping it in a box. “Ma’am,” Sarge addressed her, “sorry about the mess. We’d be glad to help clean up.” “You go to hell!” Momma cried. “My boys are somewhere out there. You come in here and ... and ...”

She dropped the cardboard, stood up straight, then wrapped her arms around herself and shuddered a weeping despair. I stood in front of her and glared at the policeman. He shook his head sadly, and followed his men into the yard.

Neighbors came knocking after the police left, but Momma refused to answer the door. I helped her make grilled cheese sandwiches with the commodity cheese, and Daddy turned up the Country Western. Lisa and I went to bed early, and I tried to locate bedbugs in the darkness. I could never find them, but could feel them crawling. In the morning I would have the red itchy bumps; at least now I knew why. The next morning, Momma said I had to go to school. Some days I was glad I couldn’t make out things with my eyes until they were a couple of feet away. This was one of those days. I felt the eyes on me, heard the sniggering, but was fairly safe in my fuzzy cave. “Did they find your brothers?” I flinched as the teacher placed her hand on my shoulder. I shook my head and stared at her hand. She gave me a reassuring pat, then returned to her desk. My girl, Jackie, wasn’t there and I was kinda glad because I felt all messed up and confused inside. I was glad she wasn’t there but, for some reason, it made me want to cry. I couldn’t remember what the teacher was writing on the board but she left me alone that day, a mercy. When the bell rang, I ran outside and stood on the corner. It would have been nice to swing that gold chain and look into the eyes she was kind enough, eager even, to share. The first thing I noticed when I entered the house was Jerry and Peter sitting on the couch. There were empty boxes stacked in a corner of the kitchen. Momma was bent over, pulling pots and pans from a cupboard. “Timmy!” she said excitedly, “We’re moving back to Colorado.” She cast Jerry a sidelong glance. “There’s no way we can stay here now.” “Wha ... Wha ...,” I mumbled. A car honked outside. Momma's hands went to her hair and fluttered about like lost birds. She grabbed her coat and purse and kissed me on the forehead. “Watch them,” she said meaningfully. “Daddy’s finishing a roof, so he’ll be home late. I have to go to work.” She kissed me again as the car continued to honk, then rushed out the door. I dropped my books on the floor and went into the living room. “What?” I asked.

“We got to ride in a police car,” Peter chirped. “But how?” I continued stupidly. “They caught us stealin’,” Jerry said, “an’ brought us home. Oh boy.” “Does Daddy know?” I asked incredulously. “He was here when they brought us,” Jerry replied. I wanted to hug him but knew he would have none of that. “Aren’t you in trouble?”

“He’ll get me later,” Jerry said matter-of-factly. “I think that policeman scared him.” We sat in silence as Peter snuggled next to Lisa on the couch. Soon they were sound asleep. Jerry put a finger to his lips, stood up and motioned for me to follow him. He opened the door and made his way clumsily down the broken cellar steps. As I hung from the creaking rail, my eyes were assaulted by a bright beam of light. I fell onto a pile of freshly-dug Earth. Jerry sat there clutching a shiny new flashlight, a self-satisfied look on his face. He reached into a bag, tossed me a Hershey bar, then took one for himself. “It’s all out there,” he murmured., “Alls you gotta do is take it.” I gobbled the Hershey and he gave me another. “You shouldn’t have run away,” I said.

“Someday they won’t catch me,” he murmured, “An’ I’ll never come back.” I licked the chocolate from my fingers. “Why’d you take Peter?” Jerry shook his head. “The little brat woke up when I came out o’ the corner. Said he’d squeal if I didn’t take him along. I woulda been better off by myself.” I crumbled a clod of dirt in my fist. “The police thought you guys were buried in here.” He put the flashlight to his chin, making a grotesque mask of his thin face. “I wish I was.” Daddy came home from work and finished the packing. He cleaned the house and made us all popcorn. I noticed his hand shaking as he sipped his coffee and stared at Jerry. Our father was a very good man when he was sober. Next day we loaded the truck and headed for Colorado, the state of our birth. Lisa and Peter rode up front in the cab of the truck with Momma and Daddy. Jerry and I sat in the back, nestled between boxes of our meager belongings. He gave me a thin smile and handed me a Hershey. “How’d you get that stuff in here?” I asked. “How’d you get it down in the hole in the first place?” A knowing grin broke his freckly face. “A guy’s gotta cover his stash; don’t tell Peter.” He looked a hundred years old in that moment. Shortly thereafter he dozed off, and I did what I’d been waiting to do since I came home from school and saw him sitting on the couch. I touched his skin with the tips of my fingers and kissed his sleeping Child’s face. He groaned deeply and touched where my lips had kissed. In a small voice he whispered, “Daddy.” Then I lay back and wrapped myself in a bedbug blanket and dreamed the dream that will haunt me for the rest of my life; where a girl with freckles, and a heart as big as her eyes, makes sweet words with her lips, and swings one end of a chain forever golden. |

|

|

| Listing Site Updates Under one of these subheadings, it's a good idea to list recent updates to my site so that visitors, especially return visitors, can check out the new stuff first. For example, I could list the date and a brief description of the update: 7/16/00 Added pictures of my vacation to the Photo page. 6/25/00 Updated the team schedule for the fall 200 season. 5/30/00 Added information about a new product my business offers. I could also list updated news about my site's topic. For example, if my site were about a particular sport, I'd could discuss the outcome of a recent competition. |

Captions for pictures Adding captions makes my pictures more interesting. |

|

Notifying Visitors of Site Enhancements Getting Rich Quick From My Site! |

Adding captions makes my pictures more interesting. Send an email |

|